Is there really a Hell?

“Of course!” you might say. Or maybe “No way!” Or you may consider the possibility and say, “Boy, I hope not.”

The belief in Hell is a basic tenet of Christianity. After all, we have been “saved” from the punishment for sin, which is Hell.

But does it really exist? Does the Bible really discuss it?

Before we answer that question, we should consider a more fundamental issue: the why. If Hell, in fact, does exist, why does it?

Here is the reason: Because God is just, He cannot let sin go unpunished. If He were to look the other way or sweep our trespasses under the rug, He would be violating His own nature. Therefore, He must punish sin, which is the task of Hell.

Now, let’s consider one more possibility: annihilation. After all, if we simply cease to exist after death, there is no purpose for Hell, right?

Annihilation is not an option

The Bible clearly rejects annihilationism. Consider Enoch, for example. Here was a guy who apparently pleased God, and suddenly he “was not.”

And Enoch walked with God; and he was not, for God took him. (Genesis 5:24)

He walked with God and God took him. It does not make sense in the context of the passage to assume that God simply annihilated him. It seems as he was being rewarded for a close walk with God.

The same goes for Elijah. Having finished up training of his protégé, Elisha, God whisked him away.

Then it happened, as they continued on and talked, that suddenly a chariot of fire appeared with horses of fire, and separated the two of them; and Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven. (2 Kings 2:11)

Where did he go? He went up into heaven (Hebrew shawmayim, a word that refers to the skies, or heavens). He did not just disintegrate into nothingness.

We find something a little more specific in Job. While he was undergoing extreme tragedy and agony, he encouraged himself by recognizing that there is something beyond this life.

For I know that my Redeemer lives, and He shall stand at last on the earth; and after my skin is destroyed, this I know, that in my flesh I shall see God, Whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another. How my heart yearns within me! (Job 19:25-27)

Job knew that at some point, after all this was over, he would, in the flesh, see God.

So, where do dead people go?

Let’s start with the Old Testament.

Old Testament: Sheol – The place of the dead

In the Old Testament, every person who died went to sheol, which was simply the place of the dead.

The Hebrew word sheol appears sixty-five times in the Old Testament and is translated as “hell,” “grave,” and “pit.” It basically means “the underworld” or “the place of the dead.” It does not specifically point out whether this place would be good or bad, and we see it used in both contexts. Neither does it necessarily refer to the physical grave, as there was another Hebrew word for that (kehber, see Gen. 50:5).

Jacob (AKA Israel) knew he would go to sheol. Not willing to lose Benjamin should something happen to him if he went with his brothers to Egypt, Jacob lamented to his sons:

But if you take this one also from me, and calamity befalls him, you shall bring down my gray hair with sorrow to the grave [sheol]. (Genesis 44:29)

When Korah led a rebellion against Moses in the desert, God punished him and his collaborators in a new (can I say groundbreaking?) way:

Now it came to pass, as he finished speaking all these words, that the ground split apart under them, and the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them up, with their households and all the men with Korah, with all their goods. So they and all those with them went down alive into the pit [sheol]; the earth closed over them, and they perished from among the assembly. (Numbers 16:31-33)

Job yearned for sheol as a reprieve from his turmoil:

Oh, that You would hide me in the grave [sheol], that You would conceal me until Your wrath is past, that You would appoint me a set time, and remember me! (Job 14:13)

The wicked will be in sheol:

The wicked shall be turned into hell [sheol], and all the nations that forget God. (Psalms 9:17)

But sheol is not just for the wicked: everyone will be there:

Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with your might; for there is no work or device or knowledge or wisdom in the grave [sheol] where you are going. (Ecclesiastes 9:10)

So, sheol is simply the place where all dead people go. Now let’s turn to the New Testament.

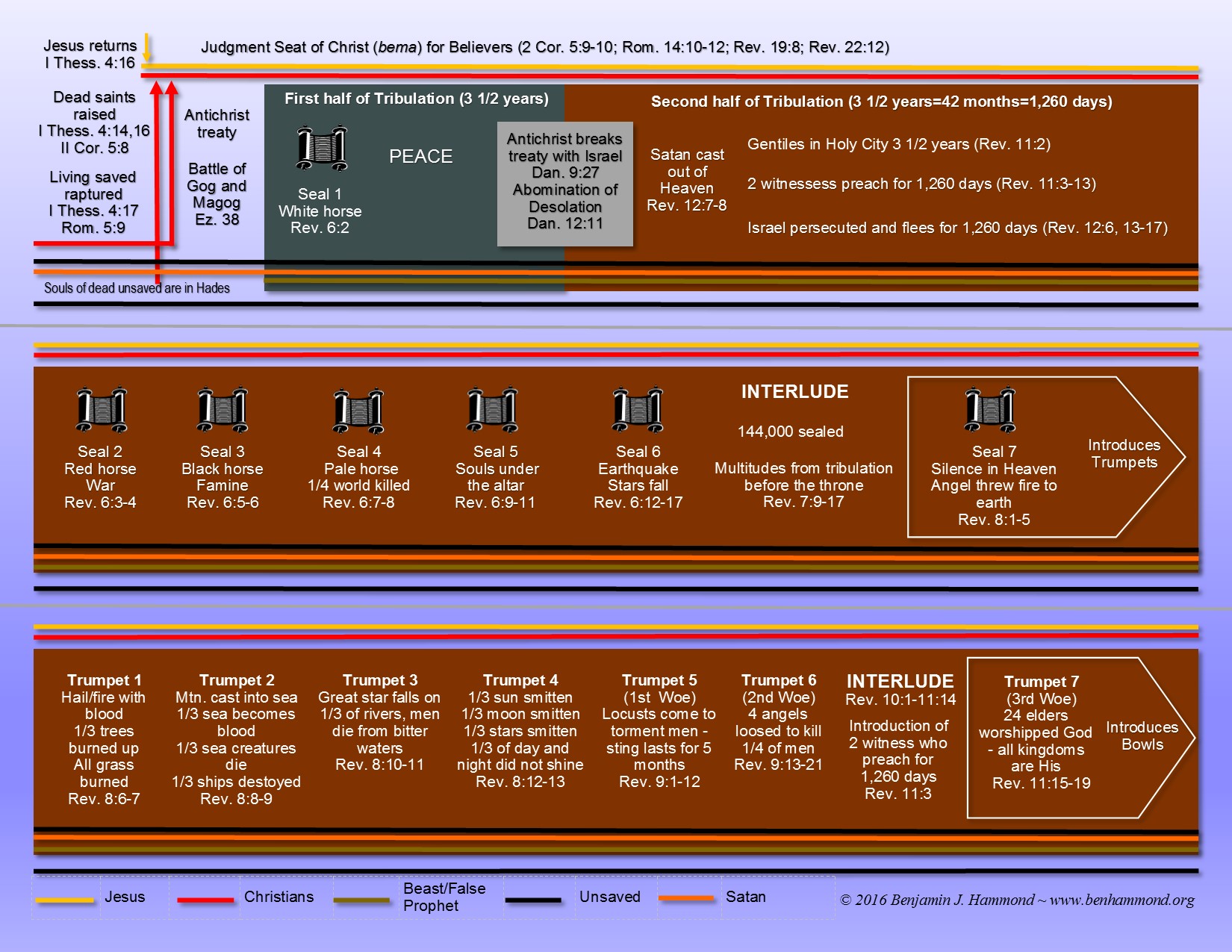

Hell in the New Testament

The New Testament, being written in Greek, uses other words. The first his hades, the Greek equivalent of sheol. Like sheol, it simply refers to the place of the dead.

Here are a few places it appears:

O death, where is your sting? O Hades, where is your victory? (I Corinthians 15:55)

Then Death and Hades were cast into the lake of fire. This is the second death. (Revelation 20:14)

When Jesus came to earth, He clarified what happens in the afterlife by utilizing a different term for what is generally described as Hell. He used the word gehenna, which literally means “Valley of Hinnom.”

The valley to which Jesus referred is situated just outside of Jerusalem. At one time, live child sacrifices to pagan gods were carried out there. Eventually it became a dump where trash and criminals’ bodies were burned. One can conjure up an image of the awfulness of such a place. When the always colorful Messiah discussed eternal punishment for sin, He provided an image that everyone could understand.

If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out and cast it from you; for it is more profitable for you that one of your members perish, than for your whole body to be cast into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and cast it from you; for it is more profitable for you that one of your members perish, than for your whole body to be cast into hell. (Matthew 5:29-30)

We could, of course, also turn to Revelation, where the eternal punishment of the wicked is described as a Lake of Fire. It is clear, then, that we all have an eternal destiny beyond this earth. As we see in the New Testament, whether that destiny is pleasant or torture is up to us, depending on whether we trust the sacrifice of Jesus as payment for our sins.