Click here to download this document in PDF form

Scroll down to view the videos on this subject or click this link

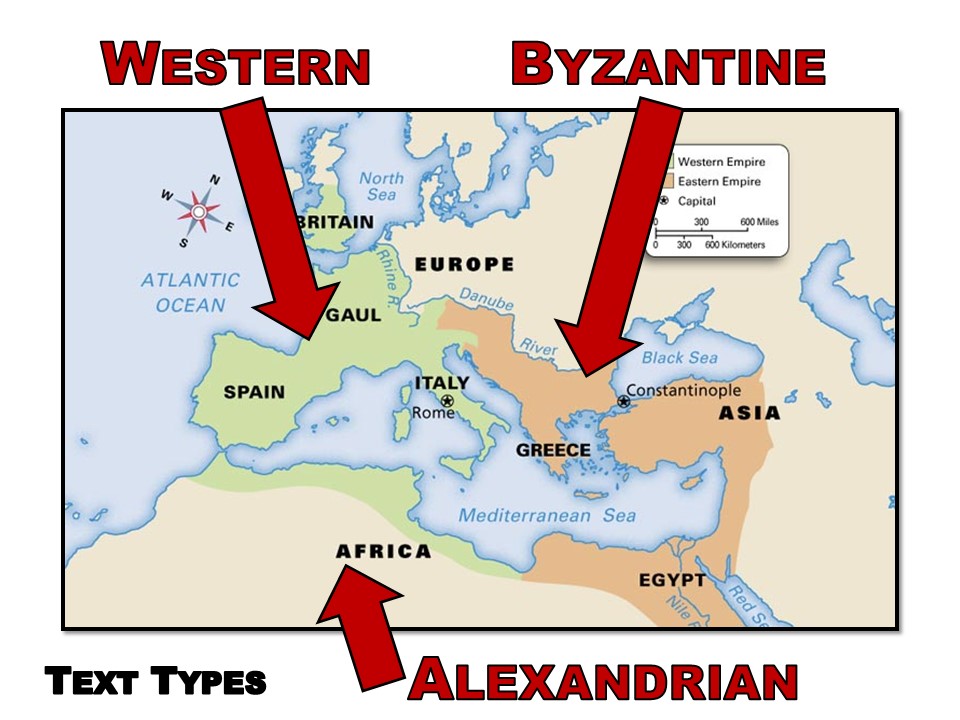

If you ever embark on a study of the transmission of the Bible through the centuries and its companion subject of Bible translations, you may find yourself faced with a critical question: do we really have God’s Word? After all, the history of the Bible is quite complex. Setting aside the differences in translation methods that greatly impact our English versions, the underlying texts muddy the waters. We no longer have the original manuscripts penned by the actual writers, so we have to rely on later copies. Of course, there are thousands of those, and to further confuse us, they vary between themselves. Textual scholars have responded to this by grouping them into “text types,” which are basically groups of texts that are similar in wording or provenance. These text types are Western, Alexandrian, and Byzantine. The following graphic depicts the origins of these text types.

The fact that we have to separate biblical manuscripts into text types reveals our conundrum. Why are they different? Which ones are right? Does one text type contain the pure, unadulterated words of Scripture? If so, which one? And which text within that text type?

The underlying question, of course, is this: did God preserve His Word for us? Or have the Scriptures been so totally corrupted that we cannot trust what we read in our modern Bibles?

Enter the doctrine of preservation.

True Christians believe that God did preserve His Word. However, we find ways to argue about how He did it. Some believe that His Word is preserved somewhere within the thousands of manuscripts, and some believe it is preserved through the “Textus Receptus” (which, by the way, is a subset of the Byzantine text and is actually its own text type). Of course, one argument for the latter is that God has promised to perfectly preserve His words through the generations, so we must have one uncorrupted line of texts. In this document, we will consider the passages that seem to indicate this promise of God.

First, however, we should define what we mean by “preservation.” The doctrine of preservation is the belief that the Scriptures have been accurately preserved throughout the generations.

Here is a slightly more detailed definition of preservation (from gotquestions.org):

The doctrine of preservation in regard to Scripture means that the Lord has kept His Word intact as to its original meaning. Preservation simply means that we can trust the Scriptures because God has sovereignly overseen the process of transmission over the centuries.[1]

We are, of course, interested in what God says about preservation. So, we begin with this question: did God promise that after the Scriptures were written, a pure and exact copy would be handed down through the generations? If so, we need to find out which one it is, embrace that one, and reject all others. If not, we should engage in textual criticism to get as close as we can to the originals.

To determine the answer to this question, we will take a deep dive into the passages typically applied to the doctrine of preservation to see what kind of promise God was making.

Passages typically used to teach preservation

Before we look at these passages, we should remind ourselves what the phrase “Word of God” means. We generally apply three meanings to that phrase:

1. God’s oral words

2. God’s written words (Scripture)

3. Jesus

The phrase “Word of God” can apply to the canon of Scripture. It can also apply to God’s oral words or even to Jesus Christ Himself. With that in mind, let us look at some passages that refer to how God will treat His “Word.”

Psalm 12:6-7

The words of the Lord are pure words, like silver tried in a furnace of earth, purified seven times. You shall keep them, O Lord, You shall preserve them from this generation forever. (Psalms 12:6-7)

In this psalm, David mourns over the disappearance of faithful men (v. 1). Because rebellious people speak evil (v. 2), he wants God to cut off their flattering lips (v. 3-4).

Then he contemplates the words of God: “For the oppression of the poor…I will arise…I will set him in the safety for which he yearns” (v. 5).

Through David, God promises that the ungodly will not win in the end. David, of course, is thrilled about this, having just lamented the scarcity of faithful men.

In his excitement, David points out how the words of God are pure (unlike the flattering lips of the wicked—v. 2), like refined silver (v. 7). In other words, they are holy and uncorrupted (like the wicked). There is no impurity in the promises of God. When God makes a promise, He will keep and preserve it.

The word “keep” (shawmar) carries the meaning of protecting, guarding, attending to, observing, or preserving. The word “preserve” (nawtsar) shares the idea of guarding, protecting, or maintaining. This word is used often in the phrases “keep thy law,” “keep my commandments,” or “keep thy heart.”

The Hebrew words shawmar and nawstar are very similar, and David may have used them because they rhyme. God will shawmer and nawtsar His promises. He will keep and preserve them. This is not a promise that everything God says will be written down and perfectly preserved through the generations. The promise is that when God says He will stand up for the oppressed, He will do it. His words are “preserved” in the sense that they will not fail.

Here is the summary of Psalm 12:6-7: David is praising God that He will stand up for the oppressed as He promised.

Isaiah 40:8

The grass withers, the flower fades, but the word of our God stands forever. (Isaiah 40:8)

If we back up a few verses for context, we will see that God has just prophesied through Isaiah that better days would come for a suffering Israel and that God’s glory would be revealed.

“Comfort, yes, comfort My people!” Says your God. “Speak comfort to Jerusalem, and cry out to her, that her warfare is ended, that her iniquity is pardoned; for she has received from the LORD’s hand double for all her sins.” The voice of one crying in the wilderness: “Prepare the way of the LORD; make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be exalted and every mountain and hill brought low; the crooked places shall be made straight and the rough places smooth; the glory of the LORD shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together; for the mouth of the LORD has spoken.” (Isaiah 40:1-5)

These verses seem to foresee the coming of John the Baptist and Jesus (all four gospel writers quote this passage in reference to John the Baptist), indicating that the restoration of Israel has something to do with the Messiah.

Then Isaiah continues…

The voice said, “Cry out!” And he said, “What shall I cry?” “All flesh is grass, and all its loveliness is like the flower of the field. The grass withers, the flower fades, because the breath of the LORD blows upon it; surely the people are grass. The grass withers, the flower fades, but the word of our God stands forever.” (Isaiah 40:6-8)

The grass turns brown. Flowers die and decay back into the dust. The word of God, however, never fades into oblivion. God does not offer empty promises that fade away. In this case, He promises that the Messiah will come and restore Israel. It will happen, period. After all, God said it would.

Isaiah’s point in this passage: God’s promise of the Messiah would come to pass (and not wither like grass).

This passage is also quoted in I Peter, so we will turn there next.

I Peter 1:23-25

…having been born again, not of corruptible seed but incorruptible, through the word of God which lives and abides forever, because “all flesh is as grass, and all the glory of man as the flower of the grass. The grass withers, and its flower falls away, but the word of the Lord endures forever.” Now this is the word which by the gospel was preached to you. (1 Peter 1:23-25)

Peter is writing to “pilgrims of the Dispersion” (see 1:1, likely primarily Jews), who have been enduring trials (1:6). He recognizes their condition as

…having been born again, not of corruptible seed but incorruptible, through the word of God which lives and abides forever, (I Peter 1:23)

They had been born again incorruptibly—never to perish—through God’s word. What does that mean?

First, note that Peter uses the Greek word logos (word) here, which indicates something that is said, a topic, a matter, or reasoning. Peter is saying that God, through His logos, declares the way of salvation, which is accomplished through the death of Jesus and applied by our faith.

This logos of God “lives and abides forever.” It is not trustworthy only until it becomes irrelevant. God has declared the way of salvation, and that will never change.

Some folks have attained positions that make every word they say extremely important. The president of the United States, for example. Every word that escapes his lips and every gaffe he makes appears on the evening news and late-night talk shows. But no one cares what an ex-president says. Sure, he’s the same guy who used to be president, but he is no longer in his position of power. What he says does not matter anymore. All his past executive orders can also be overturned. As they say, “there’s nothing more pathetic than a former president.” He has become, in many ways, irrelevant.

God, however, will never become ex-God. His term as supreme ruler of the universe will never end, so whatever He says is good forever.

To further prove his point, Peter quotes Isaiah 40:8…

because “all flesh is as grass, and all the glory of man as the flower of the grass. The grass withers, and its flower falls away, but the word of the Lord endures forever.” Now this is the word which by the gospel was preached to you. (1 Peter 1:23-25)

Here he translates “word” not with logos (which commonly indicates the message) but with rhema, which generally describes what is spoken about something.

This is Peter’s point: God’s promise of the gospel will never change because His words cannot become powerless or irrelevant.

Matthew 5:17-18

Do not think that I came to destroy the Law or the Prophets. I did not come to destroy but to fulfill. For assuredly, I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, one jot or one tittle will by no means pass from the law till all is fulfilled. (Matthew 5:17-18)

What’s up with the “jot” and “tittle?” A “jot” is translated from the Greek iota, which refers to the yod, a letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It is a tiny letter and resembles an apostrophe. It is used to refer to something very small.

Here is an example of a yod:

A “tittle” is a tiny part of a Hebrew letter that distinguishes it from another. For example, here is the resh and dalet. The dalet (on the right) is made with two strokes of the pen, resulting in a tiny jut on the right side. That is the tittle.

The phrase “jot and tittle” symbolizes detail. Jesus was promising that no detail of the Law would “pass away” before it is fulfilled. He would see to this personally, as He would be the one to fulfill it. As God in the flesh, He was the only one capable of providing an acceptable sacrifice that would appease God for the sin of mankind.

This passage, then, simply means this: Jesus promised to fulfill every requirement of the Law.

Now let us move to another passage that uses the same Greek word translated as “pass away.”

Matthew 24:35

Heaven and earth will pass away, but My words will by no means pass away. (Matthew 24:35)

In this passage, Jesus is teaching about the end times when He will return. When the events He prophesied begin to take place, be ready, because it all will happen. Here is the fuller context of His words:

Now learn this parable from the fig tree: when its branch has already become tender and puts forth leaves, you know that summer is near. So you also, when you see all these things, know that it is near—at the doors! Assuredly, I say to you, this generation will by no means pass away till all these things take place. Heaven and earth will pass away, but My words will by no means pass away. (Matthew 24:32-35)

We are accustomed to the consistent laws of nature. We can depend on the sunrise, the sunset, the water cycle, etc. Science itself depends on a predictable universe. In the end, though, we will find out that nature is temporary when God causes the heavens and the earth to “pass away.” There is one thing, however, that is dependable: God’s words. He can be trusted.

The point of this passage: The words of Jesus are more reliable than even nature.

Other passages the refer to the trustworthiness of God’s words:

Although the Scripture passages we considered above are often used to advocate the idea that God has preserved the Scriptures through a certain text, in context they actually teach that God’s word will come to pass. If He says it, you can take it to the bank. Here are a few others, just to drive the point home a bit more.

Balaam’s prophecy when Balak hired him to curse the Israelites:

God is not a man, that He should lie, nor a son of man, that He should repent. Has He said, and will He not do? Or has He spoken, and will He not make it good? Behold, I have received a command to bless; He has blessed, and I cannot reverse it. (Numbers 23:19-20)

God, speaking of His lovingkindness toward Israel, regardless of what they do:

Nevertheless My lovingkindness I will not utterly take from him, nor allow My faithfulness to fail. My covenant I will not break, nor alter the word that has gone out of My lips. (Psalms 89:33-34)

God’s words, shared through the prophet Isaiah:

So shall My word be that goes forth from My mouth; it shall not return to Me void, but it shall accomplish what I please, and it shall prosper in the thing for which I sent it. (Isaiah 55:11)

Now let’s move on to why we do believe in the doctrine of preservation.

Why we believe in preservation of the Scriptures

Did God accurately preserve the Scriptures, or are they so corrupted by man’s additions and deletions that we no longer know what they should be? I believe that God did preserve the Scriptures for three reasons.

1. Inspiration leads to preservation

2. The gospel message will never be lost

3. Historical evidence for preservation

Let’s consider each of these.

1. Inspiration leads to preservation

This is admittedly more philosophical than biblical, but if we believe that all Scripture is God-breathed, would it not make sense that He would make sure it would be accurately propagated to future generations? I happen to believe that an infinitely powerful God would be able to oversee this process. To go a step further, I believe that He is also capable of overseeing canonization: the process whereby people recognized which books should be honored as Scripture.

2. The gospel message will never be lost

In Matthew 24, Jesus is discussing what we recognize as the seven-year Tribulation, during which many will experience martyrdom and false prophets will arise. Despite this, the gospel will continue to spread.

And this gospel of the kingdom will be preached in all the world as a witness to all the nations, and then the end will come. (Matthew 24:14)

God will never allow His message to be lost. We have it now, two thousand years after Jesus walked the earth, and it will still be around during the Tribulation. After all, God offers the gift of salvation to all and desires that they receive it.

For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. (1 Timothy 2:3-4)

3. Historical evidence for preservation

This is the topic for the remainder of this study. We will consider in detail how the Bible was preserved through the generations.

Preservation through history

Before we trace how the Scriptures came to us through the centuries, we should quickly return to the idea of preservation itself. We will do this by asking the question, “How preserved is preserved?”

How preserved is preserved?

Can we say the Scriptures have been preserved if there are copy errors present? If we say they are preserved in our language, does that rule out any errors in translation? I think that when we consider the accuracy of Scriptural preservation, we need to keep three things in mind.

1. Accurate does not necessarily mean exact

We tend to think that preservation means we have exact copies of the originals, with no variations. However, even in our western mindset where we have quotes, footnotes, bibliographies, and plagiarism software, we often use generalities and claim them to be “accurate.”

For example, a friend may see you reading this particularly captivating study and ask you what it’s about. You may respond, “Ben says that God breathed out His word to people and it has been accurately preserved through generations.” While that may or may not be an exact quote of what I wrote, it accurately represents the message of this document.

We have to keep in mind, of course, that even translation into another language is not an exact science. Jesus Himself, as well as the biblical authors, may have quoted the Hebrew Scriptures in Greek or directly from the Greek Septuagint; which is itself a translated text.

The point here is that the variations that have shown through centuries of the dissemination and transmission of the documents does nothing to compromise preservation, which leads us to the next point…the differences are not really that great, anyway.

2. The differences between texts are minimal

Currently more than 5,800 early Greek New Testament manuscripts exist, comprising over 2.6 million pages. When we include the Old Testament, we have access to more than 66,000 total manuscripts and scrolls.[2]

If we add New Testament manuscripts from other languages to the 5,800 Greek New Testament manuscripts, the number swells to about 25,000.[3]

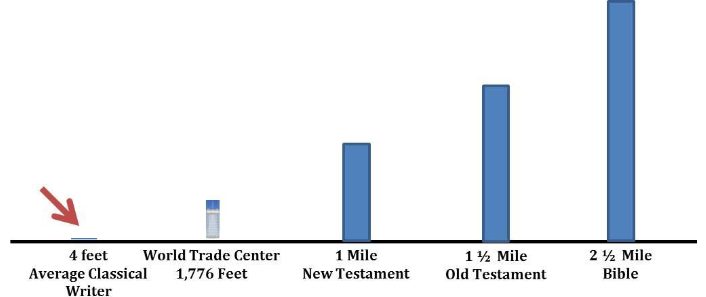

Josh and Sean McDowell cite a lecture from Daniel Wallace where he claims that the manuscripts available for the average classical writer would stack up to about four feet. In contrast, if you stacked up all the available Old and New Testament manuscripts, the stack would be 2.5 miles high.[4] The Bible is arguably the most attested document from ancient history.

Josh McDowell published the following graph depicting how biblical manuscript evidence dwarfs that of other classical writings.[5]

Here is what seems to be the challenge: between all these manuscripts (which can vary in size from a tiny fragment up to a whole document), there are many variants. In other words, they are not all identical.

When Neil Lightfoot wrote How We Got the Bible in 2003, he noted that there were likely hundreds of thousands of variants between texts. However, he stressed that that textual critics do not refer to these as “errors,” but “textual variants.” For sake of example, he assumed there are 200,000 variants between manuscripts (although he acknowledges that the number could be much higher).

This number, however, is misleading because of the way variants are counted. If one slight variant appeared in 4,000 different manuscripts, it would be counted not as one variant, but as 4,000 variants.[6]

Lightfoot then broke down the variations into three categories[7], based on how much they affect what we know of as the Bible.

1. Trivial variations which are of no consequence to the text

These variations have no effect on what we know of as the Bible. They are so minor they make no difference about its message. They include such inconsequential variations as:

- Omission or addition of words like “for,” “and,” and “the”

- Different forms of the same word

- Different spellings of the same word (as scribes adapted to their changing language)

- Grammar variations

- Spelling of proper names

- Change in order of words

We might wonder how there could be so many variations between the copies, but we must remember that it is easy to make mistakes when copying large amounts of text. It would not be impossible to accidently skip a word, repeat a word, or misjudge a previous scribe’s poor penmanship. Geisler and Nix provide a list of reasons for this, if you are interested in learning more.[8]

2. Substantial variations which are of no consequence to the text

These also do not affect what we know of as the Bible, because scholars have supposedly determined which are authentic and which are not. Generally, these variations consist of additions or deletions of a verse or verses. Lightfoot claims that these are of no consequence to our text today because our improved modern texts have settled the issues of whether or not they should be included.

We could (and maybe should) debate Lightfoot’s reasoning here, but as we will see below, neither accepting nor rejecting these passages as Scripture has any bearing on doctrine.

In case you are wondering, the most well-known passages that fit into this category are John 7:53-8:11 (the adulterous woman) and I John 5:7 (three that bear record in heaven).

3. Substantial variations that have bearing on the text

These variations affect what we know of as the Bible because their authenticity, according to Lightfoot, has not been determined.

One example is the ending of Mark (16:9-20). This section is not included in Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus, both of which are Alexandrian texts and considered to be very old. Some also claim that the vocabulary and style of writing are different than Mark’s other writings. However, it does appear in Codex Alexandrinus (which many claim to be Byzantine in the Gospels and Alexandrian in the rest of the New Testament). It also appears in many other manuscripts, and even Irenaeus (130-202 AD, influenced by Polycarp, who had known John), mentions it and acknowledges Mark as the author.[9]

Although at first glance it seems like the magnitude of manuscript variations should cast doubt on the preservation of the Scriptures, a closer look reveals that, for the most part, the differences are insignificant and do not affect our understanding of biblical doctrine.

This brings us to the next point, which is basically the same. However, it is so important that we must consider it further.

3. All doctrines remain intact between text types

Although an astounding number of biblical manuscripts exist, the variations between them are not as major as we may think and do not alter the overall message of the Bible. Spelling differences and changes in word order, of course, usually do little to change meaning, and, as we have seen, the larger disputed passages generally have little impact on theology.

For example, regarding the debated ending of Mark, the events are also discussed in other gospels. Concerning I John 5:7, the Trinity is clearly taught elsewhere in the Scriptures. As for the account of the adulterous woman in John 7, there seems to be little rejection of it as a historical account—just questions of whether it appeared in the original text.

So far, we see that although we might disagree on some of the words and maybe a few passages, we can be assured that God did preserve His word for us. There are, however, more lines of evidence to consider that show that we still have God’s Word.

The Old Testament was verified in the Dead Sea Scrolls

In the beginning of the first century AD, Jewish scholars began to recognize the importance of standardizing the text of Scripture. In the fifth to tenth centuries, a group of Jews known as the Masoretes built on this foundation and meticulously compiled and copied the Scriptures. Their work is known as the Masoretic Text (MT), the Old Testament text used in most versions of the Bible.

In 1947, a library of ancient texts was found in the caves of Qumran by the Dead Sea. Further investigation revealed that they were left by a sect called the Essenes, who live in the area about 150 B.C. to 70 A.D. The Dead Sea Scrolls, as they are called, include some books of the Old Testament. Upon examination, these texts were found to be extremely similar to the Masoretic Text, even though they were a thousand years older. This shows the high quality of the texts available to the Masoretes, as well as how precisely the Masoretes engaged in their work. The Old Testament texts available in 1000 AD were, then, very close to those in circulation before 100 AD. This serves as evidence that for those thousand years, God preserved His text.

The New Testament was circulated quickly

Remember that God never allowed the Bible to be under control of one man. The books were immediately spread out and copied to be shared with others. This kept any one person or group from purposely changing it, which is the reason the thousands of texts can be so similar.

For many of the New Testament books, this dispersion seems to have been the goal. For example, when Paul wrote to the Colossians, he told them to share letters with the Laodiceans.

Now when this epistle is read among you, see that it is read also in the church of the Laodiceans, and that you likewise read the epistle from Laodicea. (Colossians 4:16)

There is speculation about the letter “from Laodicea.” Some think it might be Ephesians, or it could be a letter that has been lost. In any case, Paul wanted these letters shared, and we can presume that they were immediately copied.

As we will see later, some very early Christians (Clement of Rome, for example, in the first century) referred to New Testament writings and treated them as Scripture. They appeared to be well-known, which was only possible if they were quickly copied and disseminated.

The New Testament chain of custody

Anyone old enough to remember, remembers it well. The stream of police cars slowly following a white Ford Bronco down a California highway in 1994 appeared on virtually every television in the nation. Riding in the passenger seat was the famed former NFL great OJ Simpson, who had been accused of killing his estranged wife Nicole and her friend Ron Goldman. Over the next several months, the trial became the primary discussion at water coolers everywhere. Eventually, a jury exonerated Simpson. Although most Americans speculated that he was guilty, the jury questioned the evidence, specifically focusing on a pair of gloves.

During the investigation, a bloody glove was found at the scene of the crime. Its match suspiciously appeared on OJ’s property. While at first this would seem like a “smoking gun” proving OJ’s guilt, questions began to swirl. Had the glove at OJ’s house been planted? It was reported that OJ’s lawyers had possession of the glove during a lunch break between court sessions. Had they tampered with it? Because of such questions, the jury could not convict him beyond reasonable doubt.

This case stresses the importance of what detectives call the “chain of custody.” Investigators log all evidence and everything that happens to it along the way. If there is any lapse in the chronology of a piece of evidence, it becomes untrustworthy.

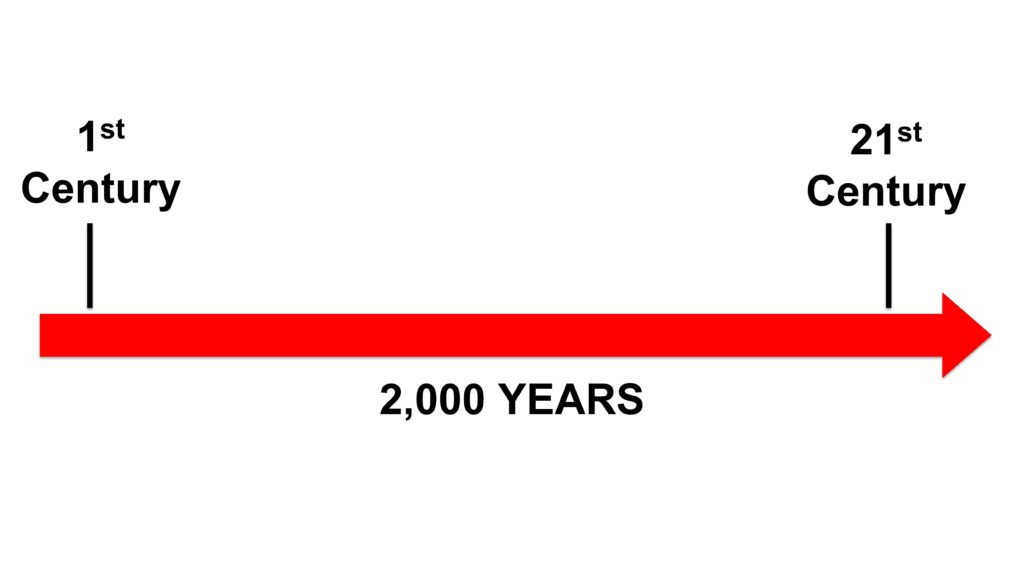

When we consider the New Testament documents, we are also interested in a chain of custody. What happened to them in the 2,000 years since they were originally written? Without having access to the original writings, can we trust the copies we have today?

As the following graph shows, we have 2,000 years of New Testament history. Our goal is to trace the chain of custody to determine if the New Testament we have today is the same as they had in the first century.

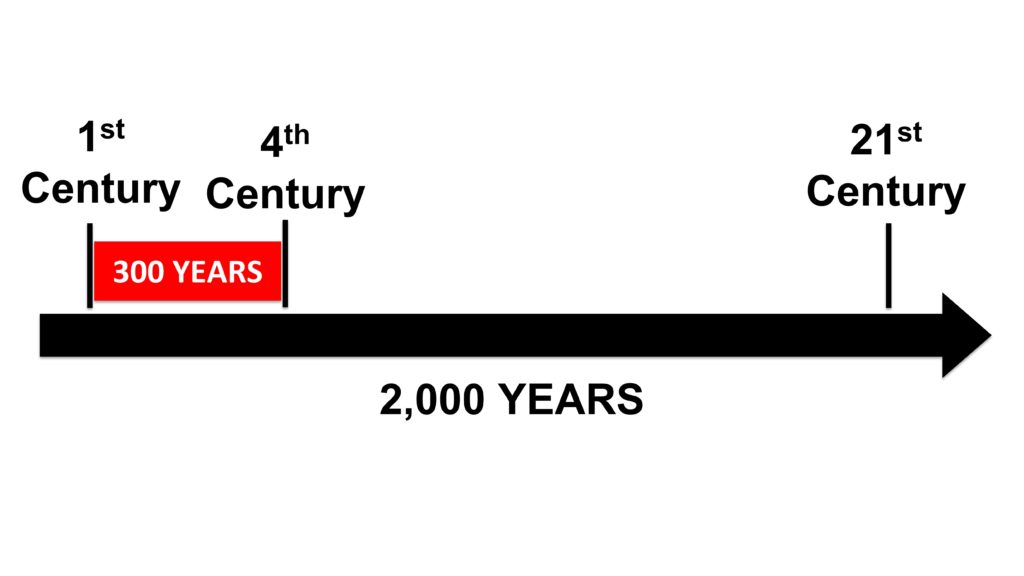

Fortunately, we do not have to follow the chain of custody for the whole 2,000 years, because we have very early texts to compare with what we have today. The most complete are Codex Vaticanus (4th century), Codex Sinaiticus 4th century), and Codex Alexandrinus (5th century).

Because we know what the New Testament looked like in the fourth century, we only have to find out what happened to it during those approximately three hundred years.

The question is this: what happened between the first and fourth centuries? Could the documents have been fabricated in the fourth century? Could they have been drastically changed somewhere along the line?

This is where we study chain of custody. What happened during those three centuries?

First, however, we have a more fundamental issue to consider: how do we know that the New Testament books were actually written in the first century?

The New Testament books: First century documents

While most Christians accept the fact that the New Testament documents were, in fact, written in the first century, some disagree. The result, of course, would be suspicion about the message of the New Testament documents. If they were not written in the first century, we should demote them to the classification of pseudepigrapha (false claims of authorship) and deem them unreliable.

So, how do we know that the New Testament was actually written in the first century? While this subject requires more space than allotted in this document, there are a few points that we can consider.

Before 70 AD (Most of the New Testament)

Nowhere in the New Testament is the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, which took place in AD 70, mentioned. An event of this magnitude surely would have come up if it had already happened, especially because Jesus Himself predicted it. This was a national disaster and not something that they would have simply overlooked.

Geisler and Turek compare the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple to the attack on the World Trade Center in New York City. If someone wrote a history of the ill-fated buildings and did not include their demise, we would assume they wrote before September 11, 2001.[10]

Of course, there are a couple exceptions. Revelation was likely written in the 90’s and does not mention the destruction of Jerusalem. John’s neglect of this event, however, does not negate the argument. It is correct that Revelation does not mention the fall of Jerusalem or the Temple, but the overall tone of the book is a pining for the “New Jerusalem” and a new Temple. The indication is that the overthrow of Jerusalem had already taken place.

Many also believe that the gospel of John was written in the late 80’s, and it also does not mention the fall of Jerusalem. A possible explanation for this is that it seems as though John’s intent was to fill in the details of the life of Jesus that the other writers left out.

The other New Testament books, however, were written before 70 AD, but we do not have to stop there. We can push them back further in time.

Before 62 AD (Paul’s writings, Luke, Acts)

According to church fathers, such as Clement of Rome, Paul was executed during the reign of Nero, which ended in 68, and the actual year of his death was likely 62. It seems to me that it would be somewhat rare for a person to write something after he died. Therefore, all of Paul’s writings, which make up the greater part of the New Testament, had to be written before 62 (or at least 68).

We can also confidently put Luke and Acts in the same boat. After all, if you were writing a history in which one person played a big role, would you not include information about his death? Luke meticulously recorded detail in Luke and Acts. He provided names, dates, and places. He even switched between “they” and “we,” depending on if he was present for the event. However, he did not record the death of Paul, his primary focus in Acts, but ended with him in a Roman prison. Therefore, the book of Acts had to be written prior to 62. Consequentially, Luke’s gospel would have been written even earlier, as Acts is the sequel to it. The other gospels were also presumably written earlier, as Luke mentioned at the outset of his gospel that others had written about the events of the life of Jesus.

We could also point out the fact that the historian Josephus claimed that James was killed in 62[11], but Luke does not record that, either. It would make sense that the death of an important figure such as James would deserve a mention in a detailed history of the early church.

As we have seen, there is plenty of evidence that the New Testament documents were written in the first century. But what happened after that? This is where we will consider the chain of custody.

Our goal in looking at the chains of custody is to determine if the New Testament documents were the same in the fourth century as they were in the first. Remember, the earliest complete texts we have today are from the fourth century. How do we know that they accurately reflect the texts from the first century? We accomplish this by looking at quotations of the Scripture during those centuries as well as the theological understandings of extrabiblical authors. If we see a chain of the same doctrine and quotations, we can be assured that the fourth century Scriptures are the same as the originals from the first century. We will also look at some less complete manuscripts that date from much earlier than the fourth century.

We will begin with the chain of custody that originates with John the Apostle.

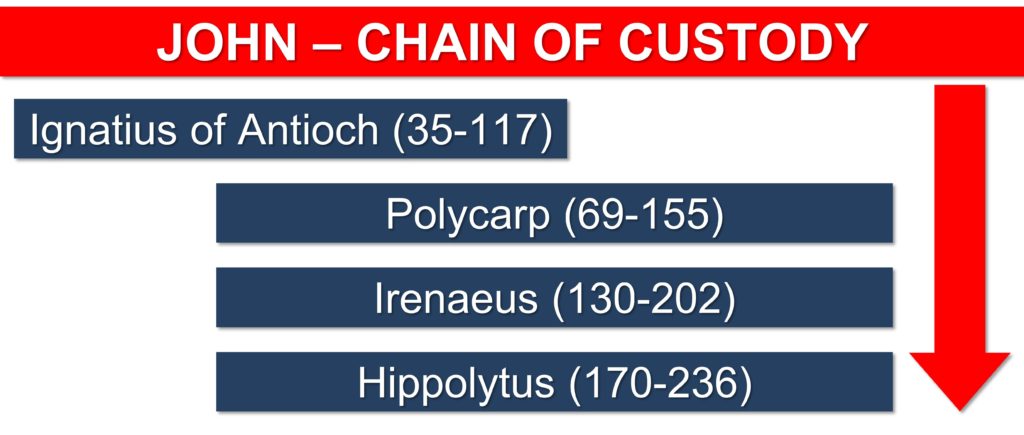

Chain of custody from John

The traceable chain of custody from John runs only into the third century, but it helps us understand both the content and theology in the New Testament during that time. We will look first at John’s disciple Ignatius of Antioch, then follow the chain of custody from Polycarp to Hippolytus.

John → Ignatius of Antioch (35-117 AD)

Ignatius will come up later in this study, so it will be beneficial to consider his close relationship with John himself. In his later life, he became the bishop of Antioch in Turkey, but in his earlier life, tradition has it that he knew John personally. Philip Schaff wrote:

That he and Polycarp were fellow-disciples under St. John, is a tradition by no means inconsistent with anything in the Epistles of either.[12]

Jerome (342-420 AD) noted in his Chronicles that:

Bishop Irenaeus writes that John the Apostle survived all the way to the time of Trajan: after whom his notable disciples were Papias, Bishop of Hieropolis, Polycarp of Smyrna, and Ignatius of Antioch.[13]

J. Warner Wallace observed:

It’s clear from Ignatius’s letters that he knew many of the apostles, as he mentioned them frequently and spoke of them as though many of his older readers also knew them.[14]

Ignatius wrote letters to the early churches, seven of which exist today (there are fifteen in circulation, but the first eight have been determined to be spurious[15]). There are two versions of each of the remaining seven, with the shorter versions being the originals.

What can we learn from Ignatius about the content of the Scriptures? Scholars claim that Ignatius either quoted or alluded to seven to sixteen New Testament books.[16] At the very least, this indicates that those books existed in the first century very much like they do today.

Here are some samples from just one of his works, his Epistle to the Ephesians.[17]

Chapter 1

He quoted from II Timothy 1:16 – “hath not been ashamed of my chain.”

Chapter 2

He quoted from I Corinthians 1:10 – “Ye may be perfectly joined together in the same mind…”

Chapter 3

He alluded to Philemon 1:8-9 – “inasmuch as love suffers me not to be silent in regard to you…”

Chapter 5

He alluded to Matthew 18:19-20 – “For if the prayer of one or two possesses such power…”

He directly quoted from Proverbs 3:34, James 4:6, and I Peter 5 – “For it is written, ‘He resisteth the proud.’”

Chapter 6

He referred to Matthew 24:25 – “we ought to receive every one whom the Master of the house sends…”

Chapter 9

He referred to I Peter 2:5 – “as being stones”

Chapter 10

He quoted from Matthew 5:5 – “blessed are the meek.”

He quoted from I Peter 2:23 – “who, when He was reviled, reviled not again…”

This is merely a sample of the references to and quotations from the New Testament by Ignatius, but they indicate his knowledge of and respect for the Scriptures, as well as the content of the New Testament books.

Ignatius also shared something interesting about the Apostles themselves. While writing his Epistle to the Romans, telling them not to rescue him from coming martyrdom, he recognized the authority of the Apostles:

I write to the Churches, and impress on them all, that I shall willingly die for God, unless ye hinder me. I beseech of you not to show an unseasonable good-will towards me. Suffer me to become food for the wild beasts, through whose instrumentality it will be granted me to attain to God. I am the wheat of God, and let me be ground by the teeth of the wild beasts, that I may be found the pure bread of Christ. Rather entice the wild beasts, that they may become my tomb, and may leave nothing of my body; so that when I have fallen asleep [in death], I may be no trouble to any one. Then shall I truly be a disciple of Christ, when the world shall not see so much as my body. Entreat Christ for me, that by these instruments I may be found a sacrifice [to God]. I do not, as Peter and Paul, issue commandments unto you. They were apostles; I am but a condemned man: they were free, while I am, even until now, a servant. But when I suffer, I shall be the freed-man of Jesus, and shall rise again emancipated in Him. And now, being a prisoner, I learn not to desire anything worldly or vain.[18]

The Apostles were, at least according to Ignatius, seen as authoritative in the first century. This indicates an early understanding of the distinctiveness of this select group, which lends credibility to the New Testament.

Now we will follow a longer chain of custody, this time through Polycarp.

John → Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna (lived 69-155 AD)

Polycarp was a contemporary and acquaintance, and maybe even a friend, of Ignatius. He mentioned in his Epistle to the Philippians that Ignatius had written to him:

Both you and Ignatius wrote to me, that if any one went [from this] into Syria, he should carry your letter with him; which request I will attend to if I find a fitting opportunity, either personally, or through some other acting for me, that your desire may be fulfilled.[19]

Note: You can read this letter from Ignatius in Epistle to Polycarp, chapter 8.[20]

Tradition has it that Polycarp knew John personally. As we saw in our discussion of Ignatius, Philip Schaff wrote

That he and Polycarp were fellow-disciples under St. John, is a tradition by no means inconsistent with anything in the Epistles of either.[21]

Irenaeus (130-202 AD) also described Papias (bishop of Hierapolis, lived 60-130 AD) as “an ancient man who was a hearer of John and a companion of Polycarp.”[22] Along with Papias, then, Polycarp would have been a “hearer of John.”

Irenaeus also said this about Polycarp (bold mine for emphasis):

But Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna, whom I also saw in my early youth, for he tarried [on earth] a very long time, and, when a very old man, gloriously and most nobly suffering martyrdom, departed this life, having always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down, and which alone are true. To these things all the Asiatic Churches testify, as do also those men who have succeeded Polycarp down to the present time,—a man who was of much greater weight, and a more stedfast witness of truth, than Valentinus, and Marcion, and the rest of the heretics. He it was who, coming to Rome in the time of Anicetus caused many to turn away from the aforesaid heretics to the Church of God, proclaiming that he had received this one and sole truth from the apostles,—that, namely, which is handed down by the Church. There are also those who heard from him that John, the disciple of the Lord, going to bathe at Ephesus, and perceiving Cerinthus within, rushed out of the bath-house without bathing, exclaiming, “Let us fly, lest even the bath-house fall down, because Cerinthus, the enemy of the truth, is within.” And Polycarp himself replied to Marcion, who met him on one occasion, and said, “Dost thou know me?” “I do know thee, the first-born of Satan.” Such was the horror which the apostles and their disciples had against holding even verbal communication with any corrupters of the truth; as Paul also says, “A man that is an heretic, after the first and second admonition, reject; knowing that he that is such is subverted, and sinneth, being condemned of himself.” There is also a very powerful Epistle of Polycarp written to the Philippians, from which those who choose to do so, and are anxious about their salvation, can learn the character of his faith, and the preaching of the truth. Then, again, the Church in Ephesus, founded by Paul, and having John remaining among them permanently until the times of Trajan, is a true witness of the tradition of the apostles.[23]

J. Warner Wallace noted this about Polycarp’s letter to the Philippians:

Polycarp also appears to be familiar with the other living apostles and eyewitnesses to the life of Jesus. He wrote about Paul, recognizing Paul’s relationship with the church at Philippi and confirming the nature of Paul’s life as an apostle.[24]

Note that Polycarp himself did not claim to know John personally, but it was the “word on the street.” Regardless, Polycarp remains a very early source for first century understanding of the New Testament. If he did not personally know the Apostles, he followed closely in their footsteps.

According to J. Warner Wallace:

Like that of Ignatius, Polycarp’s writing affirms the early appearance of the New Testament canon and echoes the teachings of John related to the nature and ministry of Jesus. Ignatius and Polycarp are an important link in the New Testament chain of custody, connecting John’s eyewitness testimony to the next generation of Christian “evidence custodians.”[25]

If Polycarp is vital to the New Testament chain of custody, what were the Scriptures he knew? As with other early writers, this question is easy to answer. For example, in his Epistle to the Philippians[26], he often quoted from the Scriptures, often stringing New Testament quotations together. Here are a few examples:

Chapter 1

He quoted from Acts 2:24 – “whom God raised from the dead, having loosed the bands of the grave.”

He quoted from I Peter 1:8 – “In whom, though now ye see Him not, ye believe, and believing, rejoice with joy unspeakable and full of glory.”

Chapter 2

He cited several Scripture passages in a row: I Peter 1:13 & Ephesians 6:14, Psalm 2:11, I Peter 1:21, I Peter 3:22 & Phil. 2:10, I Cor. 6:14, I Peter 3:9, etc.

Chapter 3

He clearly stated that he was following in the teaching of Paul.

These things, brethren, I write to you concerning righteousness, not because I take anything upon myself, but because ye have invited me to do so. For neither I, nor any other such one, can come up to the wisdom of the blessed and glorified Paul. He, when among you, accurately and stedfastly taught the word of truth in the presence of those who were then alive. And when absent from you, he wrote you a letter, which, if you carefully study, you will find to be the means of building you up in that faith which has been given you, and which, being followed by hope, and preceded by love towards God, and Christ, and our neighbour, “is the mother of us all.” For if any one be inwardly possessed of these graces, he hath fulfilled the command of righteousness, since he that hath love is far from all sin.

Chapter 7

He plainly declared his belief about Jesus, basically quoting from I John 4:3 —

“For whosoever does not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, is antichrist;” and whosoever does not confess the testimony of the cross, is of the devil; and whosoever perverts the oracles of the Lord to his own lusts, and says that there is neither a resurrection nor a judgment, he is the first-born of Satan.

Polycarp → Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon (130-202 AD)

Polycarp directly influenced Irenaeus (whose primary extant work was Against Heresies). He was born in Smyrna, where Polycarp was bishop. As we saw earlier, he wrote about Polycarp, from whom he had obviously gleaned his beliefs, at least in part.

But Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna, whom I also saw in my early youth, for he tarried [on earth] a very long time, and, when a very old man, gloriously and most nobly suffering martyrdom, departed this life, having always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down, and which alone are true. To these things all the Asiatic Churches testify, as do also those men who have succeeded Polycarp down to the present time,—a man who was of much greater weight, and a more stedfast witness of truth, than Valentinus, and Marcion, and the rest of the heretics. He it was who, coming to Rome in the time of Anicetus caused many to turn away from the aforesaid heretics to the Church of God, proclaiming that he had received this one and sole truth from the apostles,—that, namely, which is handed down by the Church. There are also those who heard from him that John, the disciple of the Lord, going to bathe at Ephesus, and perceiving Cerinthus within, rushed out of the bath-house without bathing, exclaiming, “Let us fly, lest even the bath-house fall down, because Cerinthus, the enemy of the truth, is within.” And Polycarp himself replied to Marcion, who met him on one occasion, and said, “Dost thou know me?” “I do know thee, the first-born of Satan.” Such was the horror which the apostles and their disciples had against holding even verbal communication with any corrupters of the truth; as Paul also says, “A man that is an heretic, after the first and second admonition, reject; knowing that he that is such is subverted, and sinneth, being condemned of himself.” There is also a very powerful Epistle of Polycarp written to the Philippians, from which those who choose to do so, and are anxious about their salvation, can learn the character of his faith, and the preaching of the truth. Then, again, the Church in Ephesus, founded by Paul, and having John remaining among them permanently until the times of Trajan, is a true witness of the tradition of the apostles.[27]

What did Irenaeus think about the Scriptures and what were the Scriptures he knew? His work Against Heresies was a collection of five books written between 182 and 188 AD,[28] which he wrote it primarily to combat Gnosticism. In it he alluded to up to twenty-four New Testament books.[29] Here are a few samples:

Against Heresies, Book I

Preface

He quoted from I Timothy 1:4 –

INASMUCH as certain men have set the truth aside, and bring in lying words and vain genealogies, which, as the apostle says, “minister questions rather than godly edifying which is in faith”…

He alluded to

Matthew 7:14 –

Lest, therefore, through my neglect, some should be carried off, even as sheep are by wolves, while they perceive not the true character of these men,—because they outwardly are covered with sheep’s clothing (against whom the Lord has enjoined us to be on our guard), and because their language resembles ours, while their sentiments are very different…

He quoted from Matthew 10:26 –

“For there is nothing hidden which shall not be revealed, nor secret that shall not be made known.”

Chapter 1

He referenced Luke 3:23 while discussing those who promoted Gnosticism:

And for this reason they affirm it was that the “Saviour”— for they do not please to call Him “Lord”—did no work in public during the space of thirty years, thus setting forth the mystery of these Æons.

He referred to the parable of the vineyard in Mathew 10:1-16 –

For some are sent about the first hour, others about the third hour, others about the sixth hour, others about the ninth hour, and others about the eleventh hour.

Chapter 3

In this chapter, he described how false teachers used Scripture to propagate their beliefs. He quoted from Luke 8:45 and Mark 5:31 –

The same thing is also most clearly indicated by the case of the woman who suffered from an issue of blood. For after she had been thus afflicted during twelve years, she was healed by the advent of the Saviour, when she had touched the border of His garment; and on this account the Saviour said, “Who touched me?”

He issued a string of quotes from Colossians 3:11, Romans 11:36, Colossians 2:9, and Ephesians 1:10 –

And they state that it was clearly on this account that Paul said, “And He Himself is allthings;” and again, “All things are to Him, and of Him are all things;” and further, “In Him dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead;” and yet again, “All things are gathered together by God in Christ.”

He cited from I Corinthians 1:18 and Galatians 6:14 –

Moreover, they affirm that the Apostle Paul himself made mention of this cross in the following words: “The doctrine of the cross is to them that perish foolishness, but to us who are saved it is the power of God.” And again: “God forbid that I should glory in anything save in the cross of Christ, by whom the world is crucified to me, and I unto the world.”

Chapter 8

He quoted from John 1:1-3…

For “the beginning” is in the Father, and of the Father, while “the Word” is in the beginning, and of the beginning. Very properly, then, did he say, “In the beginning was the Word,” for He was in the Son; “and the Word was with God,” for He was the beginning; “and the Word was God,” of course, for that which is begotten of God is God. “The same was in the beginning with God”—this clause discloses the order of production. “All things were made by Him, and without Him was nothing made;”

…and John 1:5 –

For he styles Him a “light which shineth in darkness, and which was not comprehended”

Of course, his writings go on and on alluding to or quoting the New Testament, making him an important link in the chain of custody, or the chain of transmission, that brought the Scriptures to us.

Norm Geisler made this point about Irenaeus:

Not only does Irenaeus cite every New Testament writer as an apostle of accredited mouthpiece for God (like an associate of an apostle), but he cites from the vast majority of the twenty-seven New Testament books. The same is true of the Old Testament. So, there is no reason to believe he rejects any one of the sixty-six canonical books of Scripture.[30]

Irenaeus → Hippolytus, Bishop of Rome (170-236 AD)

Hippolytus was a disciple of Irenaeus. Philip Schaff even remarked that “in his personal character he so much resembles Irenaeus risen again, that the great Bishop of Lyons must be well studied and understood if we would do full justice to the conduct of Hippolytus.”[31] Among his works is The Refutation of All Heresies. In this ten-volume series it is estimated that he referred to as many as twenty-four New Testament books, identifying them as Scripture.[32] Here are a few samples from Book 5, chapter 2:

He quoted from Romans 1:20-27 –

“For the invisible things of Him are seen from the creation of the world, being understood by the things that are made by Him, even His eternal power and Godhead, for the purpose of leaving them without excuse. Wherefore, knowing God, they glorified Him not as God, nor gave Him thanks; but their foolish heart was rendered vain. For, professing themselves to be wise, they became fools, and changed the glory of the uncorruptible God into images of the likeness of corruptible man, and of birds, and four-footed beasts, and creeping things. Wherefore also God gave them up unto vile affections; for even their women did change the natural use into that which is against nature.” What, however, the natural use is, according to them, we shall afterwards declare. “And likewise also the men, leaving the natural use of the woman, burned in their lust one toward another; men with men working that which is unseemly”—now the expression that which is unseemly signifies, according to these (Naasseni), the first and blessed substance, figureless, the cause of all figures to those things that are moulded into shapes,—“and receiving in themselves that recompense of their error which was meet.”

He also cited Matthew 5:45 –

He says that this (one) alone is good, and that what is spoken by the Saviour is declared concerning this (one): “Why do you say that am good? One is good, my Father which is in the heavens, who causeth His sun to rise upon the just and unjust, and sendeth rain upon saints and sinners.”

Finally, he quoted from Ephesians 5:14 –

And concerning these, he says, the Scripture speaks: “Awake thou that sleepest, and arise, and Christ will give thee light.”

After Hippolytus, we have no clear and direct evidence of the next link in the chain of custody. While it is thought by many that Origen (185-253) was either a student of or influenced by Hippolytus, the subject is debated.

Hippolytus died in 236 AD. Through his works we can see that up to that point, the church fathers recognized our current New Testament books as Scripture, and their quotations relate that they had the same writings that we have today.

As a reminder, we are attempting to determine if the fourth century manuscripts in our possession accurately reflect the originals from the first century. We have verified this in our observation of the chain of custody from John (first century) to Hippolytus (third century). However, let us now turn to another chain of custody that originates with Peter.

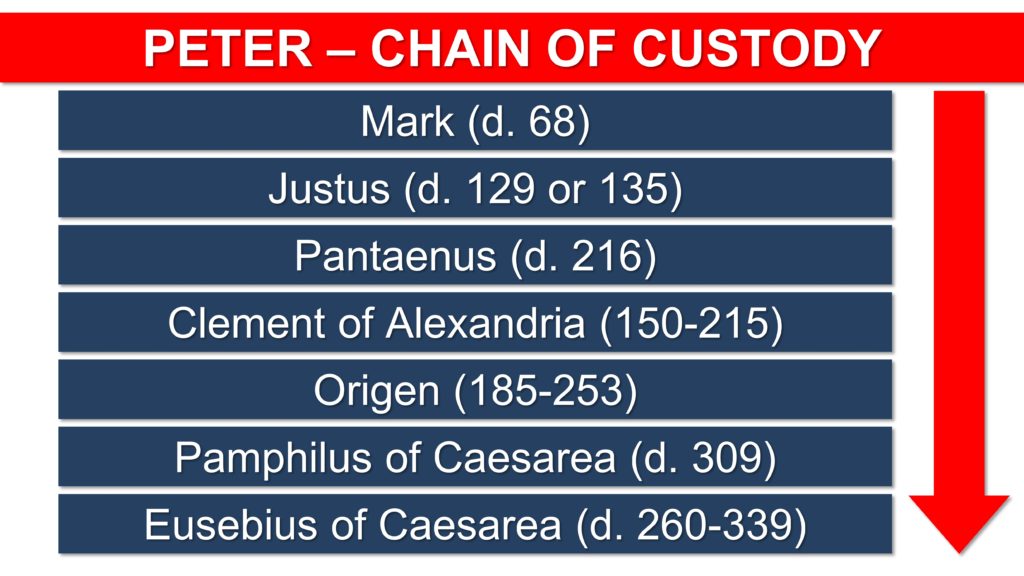

Chain of custody from Peter

The chain of custody that we can trace from Peter extends all the way to the fourth century. It begins with Peter and ends with Eusebius, whose writings are of inestimable value to the church historian.

Peter → Mark (d. 68)

Mark was, of course, a gospel writer, so we could begin this chain with him. However, it is often argued that he received his eyewitness information from Peter. This is a popular sentiment, but is it true?

Eusebius (who wrote Ecclesiastical History around 325 AD) writes that Papias (60-130) asserted that the presbyter John (not the apostle, but another John that Papias claimed wrote Revelation) claimed that Mark wrote what Peter gave him:

This also the presbyter said: Mark, having become the interpreter of Peter, wrote down accurately, though not in order, whatsoever he remembered of the things said or done by Christ. For he neither heard the Lord nor followed him, but afterward, as I said, he followed Peter, who adapted his teaching to the needs of his hearers, but with no intention of giving a connected account of the Lord’s discourses, so that Mark committed no error while he thus wrote some things as he remembered them. For he was careful of one thing, not to omit any of the things which he had heard, and not to state any of them falsely. These things are related by Papias concerning Mark.[33]

So, in the end of the first/beginning of the second century, there was the belief that Mark got his information from Peter. Irenaeus (130-202) agreed.

After their [Peter and Paul’s departure to found the church in Rome] departure Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, also transmitted to us in writing those things which Peter had preached…[34]

Eusebius also quoted Clement of Alexandria (150-215 AD), making the same claim.

As Peter had preached the Word publicly at Rome, and declared the Gospel by the Spirit, many who were present requested that Mark, who had followed him for a long time and remembered his sayings, should write them out. And having composed the Gospel he gave it to those who had requested it. When Peter learned of this, he neither directly forbade nor encouraged it.[35]

Eusebius furthermore quoted Origen (185-253):

The second [Gospel] is by Mark, who composed it according to the instructions of Peter, who in his Catholic epistle acknowledges him as a son, saying, “The church that is at Babylon elected together with you, salutes you, and so does Marcus my son.”[36]

Tertullian, writing Against Marcion (c. 208), berates Marcion for publishing only (a mutilated) Luke and ignoring the other Gospels. In doing so, he observed that Peter was Mark’s source.

The same authority of the apostolic churches will afford evidence to the other Gospels also, which we possess equally through their means, and according to their usage—I mean the Gospels of John and Matthew—whilst that which Mark published may be affirmed to be Peter’s whose interpreter Mark was.[37]

J. Warner Wallace listed several “forensic” characteristics about the book of Mark that indicate Mark’s close relationship with Peter and that the information likely came from him:[38]

- Mark mentioned Peter with prominence

- Mark identified Peter with the most familiarity

- Mark used Peter as a set of “bookends”

- Mark paid Peter the utmost respect

- Mark included details that can best be attributed to Peter

- Mark used Peter’s rough outline

Eusebius made yet another claim about this relationship between Peter and Mark:

1. And thus when the divine word had made its home among them, the power of Simon was quenched and immediately destroyed, together with the man himself. And so greatly did the splendor of piety illumine the minds of Peter’s hearers that they were not satisfied with hearing once only, and were not content with the unwritten teaching of the divine Gospel, but with all sorts of entreaties they besought Mark, a follower of Peter, and the one whose Gospel is extant, that he would leave them a written monument of the doctrine which had been orally communicated to them. Nor did they cease until they had prevailed with the man, and had thus become the occasion of the written Gospel which bears the name of Mark.

2. And they say that Peter – when he had learned, through a revelation of the Spirit, of that which had been done – was pleased with the zeal of the men, and that the work obtained the sanction of his authority for the purpose of being used in the churches. Clement in the eighth book of his Hypotyposes [a lost work] gives this account, and with him agrees the bishop of Hierapolis named Papias. And Peter makes mention of Mark in his first epistle…[39]

Then notice that he immediately moved into chapter 16, starting with:

1. And they say that this Mark was the first that was sent to Egypt, and that he proclaimed the Gospel which he had written, and first established churches in Alexandria.[40]

It is evident, then, that at least in the beginning of the fourth century, it was thought that Mark started the churches in Alexandria. This connection with Alexandria is what allows us to continue our chain of custody. Jerome (327-420) also agreed that Mark founded the church in Alexandria.

So, taking the gospel which he himself composed, he went to Egypt and first preaching Christ at Alexandria he formed a church so admirable in doctrine and continence of living that he constrained all followers of Christ to his example.[41]

Eusebius provided the succession of bishops in Alexandria:

- Mark started the churches

- Annianus took over in Nero’s 8th year (61 AD)[42]

- Abilius (c. 85 AD – served 13 years) [43]

- Cerdon (98 AD – Trajan’s first year)[44]

- Primus (died in his 12th year of service)[45]

- Justus (3rd year of Hadrian—ca 115-120) [46]

Tradition has it that that Mark died in 68 AD, and his work was carried on through his successors. We will pick up our chain of custody with Justus.

Mark → Justus

Justus may have died around 135 AD. Not only was Justus in a chain of custody through the other bishops in Alexandria, but tradition has it that he was taught and baptized by Mark himself.[47]

Justus → Pantaenus (d. 216 AD[48])

There is some belief that the Catechetical School of Alexandria[49] was founded by Mark who turned it over to Justus,[50] but there is scant historically reliable information about the beginning of the school.[51] Regardless, because it was located in Alexandria, it presumably carried on the influence of Mark.

Jerome (327-420) associated Pantaenus with this school, earning him a link in the chain of custody.

Pantaenus, a philosopher of the stoic school, according to some old Alexandrian custom, where, from the time of* Mark the evangelist the ecclesiastics were always doctors, was of so great prudence and erudition both in scripture and secular literature that, on the request of the legates of that nation, he was sent to India by Demetrius bishop of Alexandria, where he found that Bartholomew, one of the twelve apostles, had preached the advent of the Lord Jesus according to the gospel of Matthew, and on his return to Alexandria he brought this with him written in Hebrew characters. Many of his commentaries on Holy Scripture are indeed extant, but his living voice was of still greater benefit to the churches. He taught in the reigns of the emperor Severus and Antoninus surnamed Caracalla.[52]

*A footnote in this writing states that “from the time of Mark” may be translated as “following the example of Mark.”

Pantaenus → Clement of Alexandria (150-215)

Pantaenus passed along his teaching to his pupil, Titus Flavious Clement. Jerome said this about him:

Clemens, presbyter of the Alexandrian church, and a pupil of the Pantaenus mentioned above, led the theological school at Alexandria after the death of his master and was teacher of the Catechetes. He is the author of notable volumes, full of eloquence and learning, both in sacred Scripture and in secular literature; among these are the Stromata, eight books, Hypotyposes eight books… Origen is known to have been his disciple. He flourished moreover during the reigns of Severus and his son Antoninus.[53]

From his writings we get a peek into the understanding of how the gospels were viewed in the second century. While Jerome merely mentioned Clement’s Hypotyposes (which is lost to us), Eusebius quoted from it:

He said that those gospels were first written which contain the genealogies [i.e. Matthew and Luke], but that the Gospel according to Mark took shape as follows: Peter had publicly proclaimed the word at Rome and told forth the gospel by the Spirit. Then those present, who were many, besought Mark, as one who had accompanied Peter for a long time and remembered the things he had said, to make a written record of what he had said. Mark did this, and shared his gospel with those who made the request of him. When Peter came to know it, he neither vigorously forbade it nor advocated it. But John last of all (said the tradition), aware that the ‘bodily’ facts had been set forth in the [other] gospels, yielded to the exhortation of his friends and, divinely carried along by the Spirit, composed a spiritual gospel.[54]

In addition to being further evidence for Peter’s influence on Mark, this quote shows that Clement recognized the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. He also recognized the gospel of John, as we see by a quote of Clement by Eusebius:

But, last of all, John, perceiving that the external facts had been made plain in the Gospel, being urged by his friends, and inspired by the Spirit, composed a spiritual Gospel.[55]

Clement, in his Stromata, recognized that Luke wrote Acts. He wrote:

…as Luke in the Acts of the Apostles relates that Pau said, “Men of Athens, I perceive that in all things ye are too superstitious.”[56]

Clement of Alexandria → Origen (185-253)

As mentioned above by Jerome, Origen was a disciple of Clement.

Origen is known to have been his disciple. He flourished moreover during the reigns of Severus and his son Antoninus.[57]

Here is some further information about Origen given by Jerome:

When only eighteen years old, he undertook the work of instructing the Catechetes in the scattered churches of Alexandria. Afterwards appointed by Demetrius, bishop of this city, successor to the presbyter Clement, he flourished many years… It is known that before he went to Cæsarea, he had been at Rome, under bishop Zephyrinus. Immediately on his return to Alexandria he made Heraclas the presbyter, who continued to wear his philosopher’s garb, his assistant in the school for catechetes.[58]

According to Jerome, then, Origen was put in charge of the school in Alexandria, which carried on the influence of Peter and Mark.

It is not difficult to determine what Origen believed about the Scriptures, so for sake of time we will not go into detail, except to mention that Eusebius listed the books that Origen accepted as canonical.[59]

Origen → Pamphilus of Caesarea (martyred Feb. 16, 309 AD)

Pamphilus was such a disciple of Origen that he wrote a five-volume treatise (along with Eusebius, who later wrote a sixth) called Apology for Origen.

Jerome (327-420) has something interesting to say about Pamphilus:

Pamphilus the presbyter, patron of Eusebius bishop of Cæsarea, was so inflamed with love of sacred literature, that he transcribed the greater part of the works of Origen with his own hand and these are still preserved in the library at Cæsarea. I have twenty-five volumes of Commentaries of Origen, written in his hand, On the twelve prophets which I hug and guard with such joy, that I deem myself to have the wealth of Croesus. And if it is such joy to have one epistle of a martyr how much more to have so many thousand lines which seem to me to be traced in his blood. He wrote an Apology for Origen before Eusebius had written his and was put to death at Cæsarea in Palestine in the persecution of Maximinus.[60]

Unfortunately, the only work of Pamphilus that remains is his first book of the Apology for Origen series, translated into Latin by Rufinus.

Origen was apparently a controversial figure, indicated by the fact that Pamphilus defended his Christology. The following is part of the excerpt from the Amazon description of the English translation of this book:

Written from prison with the collaboration of Eusebius (later to become the bishop of Caesarea), the Apology attempts to refute accusations made against Origen, defending his views with passages quoted from his own works. Pamphilus aims to show Origen’s fidelity to the apostolic proclamation, citing excerpts that demonstrate Origen’s orthodoxy and his vehement repudiation of heresy. He then takes up a series of specific accusations raised against Origen’s doctrine, quoting passages from Origen’s writings that confute charges raised against his Christology. Some excerpts demonstrate that Origen did not deny the history of the biblical narratives; others clarify Origen’s doctrine of souls and aspects of his eschatology.[61]

Pamphilus of Caesarea → Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 260-339)

Eusebius was the bishop of Caesarea from about 314 until his death in 339. He wrote Ecclesiastical History, published around 325, which described the history of the church from Christ until the peace in the church under Constantine in 313.

Jerome (327-420) says this about Eusebius:

Eusebius bishop of Cæsarea in Palestine was diligent in the study of Divine Scriptures and with Pamphilus the martyr a most diligent investigator of the Holy Bible. He published a great number of volumes among which are the following: Demonstrations of the Gospel twenty books, Preparations for the Gospel fifteen books, Theophany five books, Church history ten books, Chronicle of Universal history and an Epitome of this last. Also On discrepancies between the Gospels, On Isaiah, ten books, also Against Porphyry, who was writing at that same time in Sicily as some think, twenty-five books, also one book of Topics, six books of Apology for Origen, three books On the life of Pamphilus, other brief works On the martyrs, exceedingly learned Commentaries on one hundred and fifty Psalms, and many others. He flourished chiefly in the reigns of Constantine the Great and Constantius. His surname Pamphilus arose from his friendship for Pamphilus the martyr.[62]

It is abundantly clear that Eusebius knew Scripture as he recorded the views of the church fathers toward it. He provided lots of information about how Christians were grappling with which books should be canonized.

Eusebius anchors this chain of custody because he lived in the fourth century, which is when Codex Sinaiticus was copied. We therefore have a chain of custody from the Apostles to the oldest complete texts in our possession, and we have seen quotations from New Testament books scattered throughout those centuries. There was no time when the New Testament or its message was lost then re-introduced by someone who may have corrupted it.

We can, however, go a step further. While our oldest complete manuscripts date from the third and fourth centuries, we have plenty of actual New Testament text dating all the way back to the second century.

Early manuscript evidence

St. John Fragment, P52 (125-200 AD)

One of the oldest manuscripts available is P52, a tiny papyrus fragment of the gospel of John. It was found in Egypt in 1920 and dates from between 125 and 200 AD, and measures about 3.5 X 2.5 inches. It contains the beginning of seven lines from John 18:31-33 on the front, and on the back is the ends of lines from John 18:37-38.[63] This is an inestimably valuable fragment as it reveals both the existence and some of the wording of the Gospel of John in the second century.

It is housed at the John Rylands Research Institute and Library at the University of Manchester.

P46 (c. 200 AD)

In the 1930s, a manuscript was found and labeled as P46. It was determined to be from 125-200 AD. Some of its leaves are in the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin and others are located at the University of Michigan.[64] While some of it has been destroyed or lost, eighty-six of its leaves remain. It contains the final eight chapters of Romans, the whole book of Hebrews, most of I & II Corinthians, the whole text of Ephesians, Galatians, Philippians, and Colossians, and two chapters of I Thessalonians.

P45 (early 3rd century AD)

P45 is the designation for a thirty-leaf papyrus manuscript that was acquired by Chester Beatty in the 1930s. It originally contained all four gospels as well as Acts, but because of its age, much of it has been lost. In addition to it being one of the earliest extant manuscripts, it is significant because it is the earliest collections of all four gospels in one volume. It is currently located at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, except for one leaf which resides at the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

P4 (2nd – 3rd century AD)

P4, which currently resides at the Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris, is a papyrus document that contains much of the first six chapters of the Gospel of Luke. It was found in the 1880s and dates from the second to third century AD.

P75 (third century AD)

This papyrus manuscript has only 102 of its pages remaining and contains most of the Gospels of Luke and John. It was found in the 1950s and now is kept in the Vatican Library.

P66 (200 AD)

This manuscript includes most of the Gospel of John and is dated around 200 AD (although some locate it in the beginning of the fourth century). It was discovered in 1952 in Egypt and currently resides in the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana (Bodmer Library) in Switzerland.

P72 (3rd – 4th century AD)

This manuscript, which also is currently housed at the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana in Switzerland, consists of ninety-five leaves. It contains I & II Peter and Jude and is thought to be the earliest extant manuscripts of these books.

P47 (200 – 250 AD)

This manuscript belongs to the Chester Beatty collection and resides at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. It dates to the early third century AD and contains most of Revelation 9-17.

As we can clearly see, there is ample evidence that the New Testament existed remarkably close to its current form very early—in some cases, barely over (or even less than) a hundred years after the original autographs were penned. While a hundred years may seem like a long time to us, it is miniscule in the criticism of ancient texts.

Now we will turn our attention from the written Scriptures to the gospel message itself. Did people in the first few centuries after Christ have the same gospel that we have today? Did God preserve the gospel message, even outside of the biblical text?

Early extrabiblical testimony of the gospel message

We do not need, of course, any kind of extrabiblical testimony to verify the message of the New Testament texts. However, we may meet people who claim that the biblical text has become so corrupted that we can no longer be assured of its message. To dispel this notion we can consider what Christians who were not biblical writers believed in the first few centuries after Christ.

Clement of Rome (30-100 AD)

As bishop of the church at Rome, Clement was considered a pope. It has been speculated that he could have been at Philippi with Paul.[65] While this cannot be verified, there is general agreement that he was the Clement referred to by Paul (Philippians 4:3).[66] According to Schaff, this was the opinion of Eusebius.[67]

Clement clearly recognized the authority of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. Around 96 AD, he wrote what we know of as the First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians (which, by the way, often appears in early canonical lists). At that time he had access to I Corinthians and saw it as authoritative and acknowledged that it had been written “under inspiration of the Spirit.”

Take up the epistle of the blessed Apostle Paul. What did he write to you at the time when the Gospel first began to be preached? Truly, under the inspiration of the Spirit, he wrote to you concerning himself, and Cephas, and Apollos, because even then parties had been formed among you.[68]

Clement’s writing is full of Scripture quotations, both from the Old and New Testaments. He obviously respected Scripture and believed the gospel message. In fact, in I Clement he warned about false teachers who pervert the truth. In doing so, he gave an indication of some specific things he believed. As one of the earliest believers on record, we can see that his theology was overwhelmingly the same as ours today. He clearly believed in the following:

- The resurrection of Jesus and a future resurrection

Let us consider, beloved, how the Lord continually proves to us that there shall be a future resurrection, of which He has rendered the Lord Jesus Christ the first-fruits by raising Him from the dead.[69]

- Justification through faith rather than works

And we, too, being called by His will in Christ Jesus, are not justified by ourselves, nor by our own wisdom, or understanding, or godliness, or works which we have wrought in holiness of heart; but by that faith through which, from the beginning, Almighty God has justified all men; to whom be glory for ever and ever.[70]

Ignatius of Antioch, Bishop of Antioch (35-117 AD)

Because Ignatius, as we have seen, was a disciple of John, he serves as a valuable source of first century doctrine. What did he believe about Jesus? While his letters to churches were designed for encouragement and instruction for living rather than doctrinal treatises, his warnings about heresy betray his concern for the truth. For instance, in his Epistle to the Trallians, he offers this admonition:

I therefore, yet not I, but the love of Jesus Christ, entreat you that ye use Christian nourishment only, and abstain from herbage of a different kind; I mean heresy. For those [that are given to this] mix up Jesus Christ with their own poison, speaking things which are unworthy of credit, like those who administer a deadly drug in sweet wine, which he who is ignorant of does greedily take, with a fatal pleasure leading to his own death.[71]

Speaking about false teachers, he instructs his readers to

Be on your guard, therefore, against such persons. And this will be the case with you if you are not puffed up, and continue in intimate union with Jesus Christ our God, and the bishop, and the enactments of the apostles.[72]

If Ignatius was concerned about departure from correct doctrine, what was the correct doctrine he believed? Fortunately, he tells us.

- The deity and humanity of Jesus

There is one Physician who is possessed both of flesh and spirit; both made and not made; God existing in flesh; true life in death; both of Mary and of God; first passible and then impassible,—even Jesus Christ our Lord.[73]

For our God, Jesus Christ, was, according to the appointment of God, conceived in the womb by Mary, of the seed of David, but by the Holy Ghost.[74]

Now the virginity of Mary was hidden from the prince of this world, as was also her offspring, and the death of the Lord; three mysteries of renown, which were wrought in silence by God. How, then, was He manifested to the world? A star shone forth in heaven above all the other stars, the light of which was inexpressible, while its novelty struck men with astonishment. And all the rest of the stars, with the sun and moon, formed a chorus to this star, and its light was exceedingly great above them all. And there was agitation felt as to whence this new spectacle came, so unlike to everything else [in the heavens]. Hence every kind of magic was destroyed, and every bond of wickedness disappeared; ignorance was removed, and the old kingdom abolished, God Himself being manifested in human form for the renewal of eternal life. And now that took a beginning which had been prepared by God. Henceforth all things were in a state of tumult, because He meditated the abolition of death.[75]

Especially [will I do this] if the Lord make known to me that ye come together man by man in common through grace, individually, in one faith, and in Jesus Christ, who was of the seed of David according to the flesh, being both the Son of man and the Son of God…[76]

- The virgin birth of Jesus

Again, as quoted above: