Click here to begin at Section 1: History of the Bible

Click here to begin at Section 1: History of the Bible

Now that we have considered the matter of the underlying texts, we have another dilemma to solve. We understand that some variations in Bible versions are a result of slightly different texts, but how can similar thoughts be worded so differently in different versions?

The answer to that question is clear for those who have dabbled in any way with languages. If you were born and raised in the United States, it is very possible that you know only one language, English. You may also know enough words in Spanish to get a few ideas across to your friends from the south, but that’s about it. However, once you begin trying to fluently transfer detailed thoughts from one language into another, you find that it is difficult, if not impossible. Bible translation is no different. Even if we only had one underlying biblical text, we would still have various translations.

The first thing that we must understand is that we cannot translate between languages perfectly. Word order, idioms, and sentence structure vary greatly between languages.

I have to admit that while I have dabbled in a few other languages, including Hebrew and Greek, I am fluent only in English. I have, however, learned sign language and can interpret for the deaf. This is not as easy as it may appear. A good interpreter will do much more than learn signs that go with spoken words. Because deaf people cannot hear, many of our idioms and other figures of speech make no sense to them. Therefore, the interpreter needs to listen to the speaker, determine what he means, and transfer it to signs and expressions that will be comprehensible to the deaf person.

That is exactly the dilemma that is faced by Bible translators. What is the best way to take the meaning of the biblical text and put it in such a way that it can be understood?

The answer to this question is not an easy one, and its difficulty is amplified because of the importance of the Word of God. How the translation is carried out can have eternal ramifications. To assist us in our understanding of Bible translation, let’s first look at the words themselves.

Words can have various translations

If you enjoy writing, you are intimately familiar with synonyms. For those of you who barely squeaked past your English classes, synonyms are words that have basically the same meanings. Without synonyms, books would be quite boring. However, this poses a problem for translators. When several words can be used, which one should be chosen?

One example of this is the Greek word agape, which is one of the words that can be translated as “love.” However, in I Corinthians 13, the famed “love chapter,” the King James translators inserted the word “charity” instead of “love.” While in our day “charity” generally carries more of the idea of an organization that helps people, it technically means the same as “love.” Those translating from Greek to English have a choice. The KJV translators chose “charity” while most other translators chose “love.”

Occasionally you may hear that a certain Bible version is a transliteration of the original Greek or Hebrew. While this sounds pious, it simply is impossible. Transliteration is the process of rendering the sounds of a word in one language into the same sounds in another language. For example, our word “deacon” comes from the Greek word diakanos, which means “servant” or “minister.” While this word would be strictly transliterated as “diakanos,” in English we use the term “deacon.”

Another word that we have transliterated from the Greek is the word “angel,” which appears in the Greek as angelos. Although this word simply means “messenger,” in our minds we picture a cute and cuddly child or a beautiful woman with wings. Never mind that when the gender of angels is mentioned in the Bible, it is always masculine. With this in mind, when the messages of Revelation are given to the angelos of each church, are we talking about a heavenly being with a halo and wings, or could it be a human messenger, such as the pastor? Furthermore, remember reading about Paul’s thorn in the flesh? If we think that our Bibles are transliterated, this thorn in the flesh would be an angel. Specifically, the “angelos of Satan to buffet me” (II Corinthians 12:7).

Finally, if we mistakenly use the term “transliteration,” then John the Baptist should also be among the angels. After all, God said about him that “I send my angelos before your face . . .” (Mark 1:2). In both II Corinthians and Mark 1, all major versions correctly interpret angelos as “messenger.” It is obvious, then, that individual words can be translated differently, depending on the interpretation of the translator.

Since we now know that words cannot always be directly translated from one language into another, we need to tackle the bigger question. Can ideas be precisely transferred between languages? This leads us to the second main factor in determining which translation we should use—the translation method employed by the translators.

Difference in translation methods

If we set out to determine which is the most accurate Bible version available, we first have to define the term “accurate.” Are we looking for the version that best represents the wording of the original, or the one that most accurately represents the message of the original? All translators have to answer this question as they embark on their work. The answer will determine which method of translation will be used.

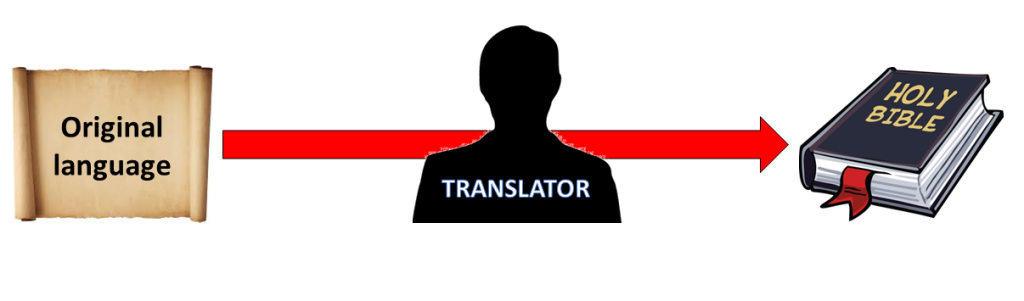

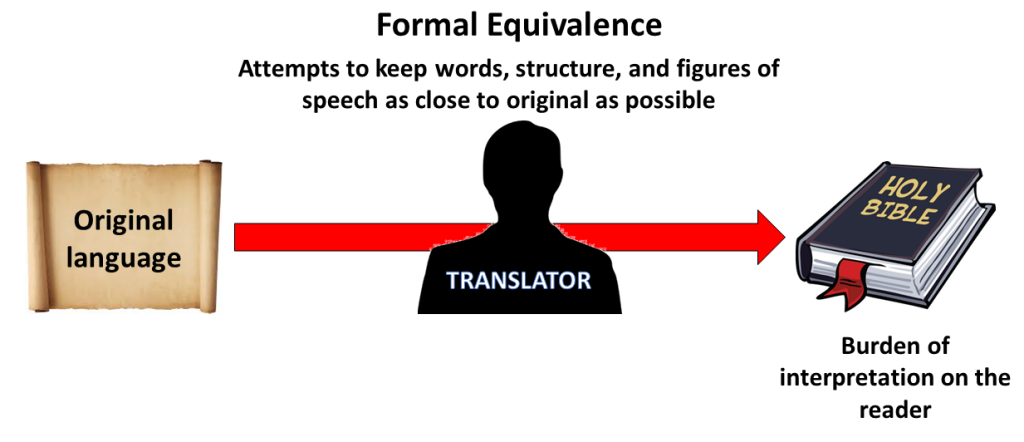

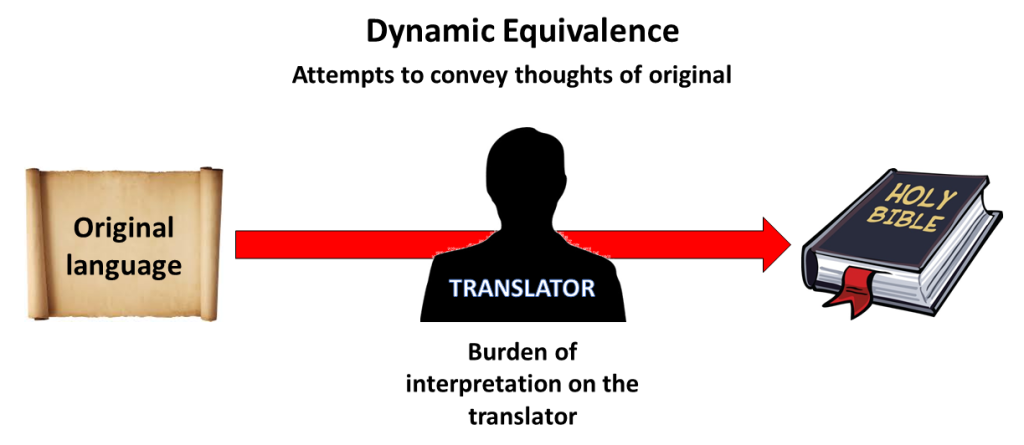

A translator is charged with a very difficult job—helping people of one language understand what was written in another. Essentially, he stands between them as the mediator. The message has to go through him to reach the reader.

The method the translator uses to do this will have a critical impact on the final translation. The methods of translation are formal equivalence, dynamic equivalence, and paraphrase. Let’s take a quick look at each of these to see how they cause variety in translation.

The method the translator uses to do this will have a critical impact on the final translation. The methods of translation are formal equivalence, dynamic equivalence, and paraphrase. Let’s take a quick look at each of these to see how they cause variety in translation.

Formal equivalence

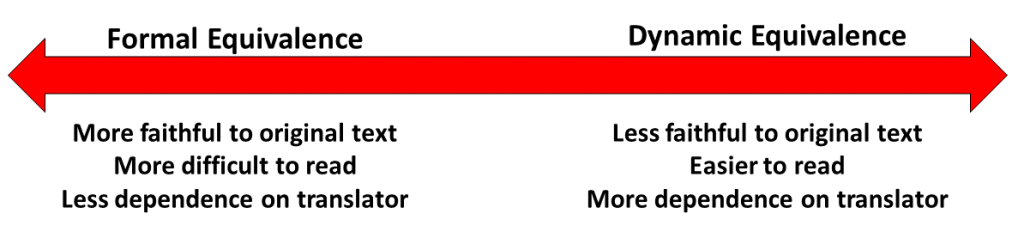

Using the method of formal equivalence, translators attempt to reproduce the original language in as close to a word-for-word manner as is possible. The positive side of this approach is that it results in a text that is more faithful to the original. It stresses the importance of the words of the Bible rather than simply the ideas,[i] which is important if we accept verbal inspiration. While the outcome is a text that is often more difficult to understand, the reader can be assured that, at least in most places, the reading is closely aligned with the original.

The downside of formal equivalence is that the resulting text may be more difficult for the readers to comprehend. It may include figures of speech that, directly translated, are meaningless without explanation. Another problem with attempting to adhere to strict formal equivalence is that it simply is not possible. As we have already noted, it is impossible to translate word-for-word from one language into another. Some words will have to be deleted or added to make the passage flow correctly in the target language. In the King James Version, many of these additional words are indicated by the use of italics.

Positives of formal equivalence:

Positives of formal equivalence:

- More faithful to the original

- Recognizes verbal inspiration

- Less dependence on the interpretation of the translator

Negatives of formal equivalence:

- More difficult to understand

- Idioms and figures of speech may not make sense

- More interpretation by the reader

- Strict formal equivalence is impossible

Popular Bible versions that use formal equivalence:

- King James Version (KJV)

- New King James Version (NKJV)

- New American Standard Bible (NASB)

- English Standard Version (ESV)

Dynamic equivalence

The second method of translation is dynamic equivalence (aka functional equivalence). With this method, the translator considers the meaning behind the original text and attempts to convey this meaning to the reader of the target language. The goal is to produce the same effect on the modern readers that the original readers experienced.[i] The disadvantage of this method is that, in order to get the meaning across, the words of original Scripture must be changed much more than with formal equivalence. On the positive side, it makes for a much more readable text. With dynamic equivalence, the burden of interpretation of the original text is on the translator, while with formal equivalence, it falls upon the reader.

Positives of Dynamic Equivalence:

Positives of Dynamic Equivalence:

- Easier to understand (more readable)

- Less interpretation by the reader

Negatives of Dynamic Equivalence:

- Less faithful to the original

- More dependent on the interpretation of the translator

Popular Bible versions that use dynamic equivalence:

- New International Version (NIV)

- New Living Translation (NLT)

An example of dynamic equivalence can be found in Romans 7:18. The KJV, using formal equivalence, reads, “For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh,) dwelleth no good thing…” The NIV, utilizing dynamic equivalence, records the same passage as “For I know that good itself does not dwell in me, that is, in my sinful nature.” The Greek word (sarx) translated as “flesh” and “sinful nature” in these respective versions literally means “flesh.” Here is the question: Are we sinners because we have a sinful nature that hangs with us throughout life, or do we sin because we are still living in a sinful physical body? Using dynamic equivalence, the NIV translators (whether correct or not) are able to interject their opinion into the text. The versions that translate this verse literally (KJV, NKJV, ESV) simply translate the word as “flesh” and allow the reader to make the decision.

Because of the differences between languages, it is impossible to have a completely formal or dynamic translation. Every translation falls some place on the continuum between the two. The closer a translation lies toward formal equivalence, the more difficult it will be to read, but the more faithful it will be to the original text. On the other hand, the closer it lies toward dynamic equivalence, the easier it will be to read, but more of the translators’ interpretation will be evident.

A paraphrase is more of a commentary than a translation. This method takes only the ideas from the original text, and is not bound by specific words and phrases. Examples of paraphrases include The Living Bible by Kenneth Taylor and The Message by Eugene Peterson.

Click here to see the next section: How to Choose a Translation

Click here to download all four sections in PDF

Section 1: History of the Bible

Section 2: Underlying Texts

Section 3: Methods of Translation

Section 4: How to Choose a Translation

[i] D. A. Waite, Defending the King James Bible: A Four-Fold Superiority (Collingswood, NJ: The Bible for Today Press, 1992), 89.

[ii] William W. Klein, Craig L. Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2004), 126.